Over the next few days (weeks?), I will post excerpts from my book Going Viral: Zombies, Viruses, and the End of the World. Taking a look at these fictional narratives before and even during an outbreak can help us see what to do and, more important, what not to do in real life. They can also remind us—even while this all feels so scary—that we have seen this before.

In the outbreak narrative, the threat always comes from the outside in, spread via physical contact, breathing, technology, science, and/or conspiracy, but almost always originating in Asia or Africa, traveling from east to west.

Outbreak narratives allow for and encourage the stigmatizing of individuals or locations deemed contagious or ripe for “plague breeding.” This method of stigmatizing individuals or locations can be seen as a retaliation against the more homogeneous unity advocated by globalization, a way to redraw lines rendered meaningless by the process of globalization. Othering also becomes a way of creating reassurance that the virus is only meant for “at risk” people, enforcing a sense of difference and distance.

Disease is consistently imagined as a foreign threat, traveling from the outside in, with—as Geddes Smith, author of Plague on Us, argues—quarantines as little more than attempts “to put a fence around an entire nation.”

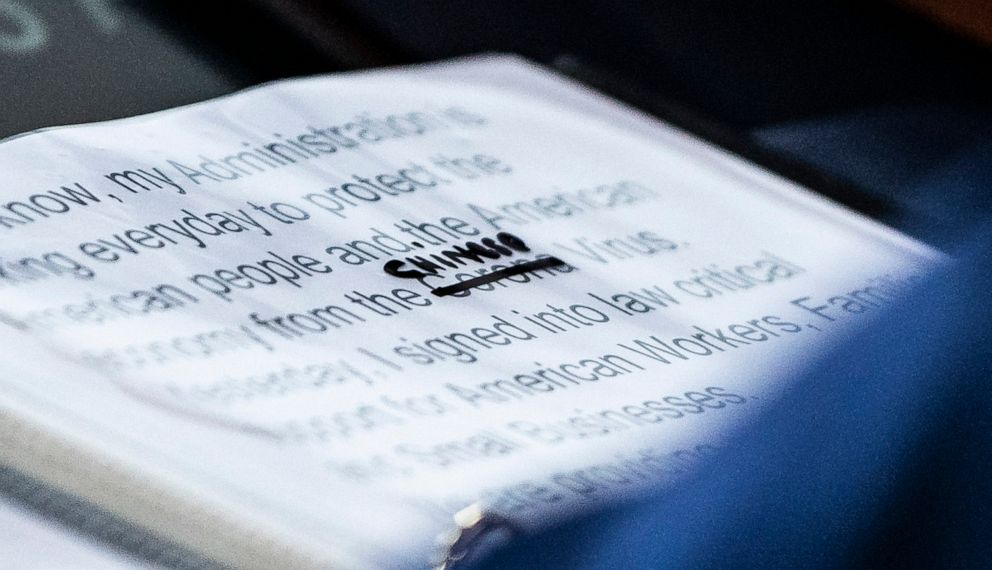

A close up of President Donald Trump’s notes shows where the word corona in “Corona Virus” was crossed out and replaced with “Chinese” as he appears with his coronavirus task force during a briefing at the White House on March 19, 2020, in Washington.

During the 1990s, it was common for the viral threat to come from an African country, even if it is was repurposed by the American military as a bioweapon, as in the case of Outbreak (Petersen, 1995). Not only does the virus come from an overtly primitive and dirty African village, but it is then transferred to “the pristine shores” of America via monkey, smuggled in by an Asian man, conveying layers of stigma and negative association.

In Contagion (Soderbergh, 2011), the virus comes from Asia—linked to the country’s alleged lack of hygiene among food workers and the underclass—even if the spread westward is due to an American company and an American blonde.

In World War Z (the book, written by Max Brooks and published by Three Rivers Press in 2007), the outbreak begins in China; however, in World War Z (the movie, directed by Marc Foster and released in 2013), the outbreak begins in South Korea. Thomas R. Feller posits that the reason for this change is the fiscally responsible reason that “China constitutes the world’s second largest movie market after the US and the filmmakers did not wish to offend the Chinese authorities who could ban the film from being shown there.”

In the miniseries Covert One: The Hades Factor (CBS, 2006), the virus was developed by Americans but spread by treacherous Muslims. The racial profiling may shift, but the other (whatever his or her skin tone) remains just as threatening, just as stigmatized.

In both real life and in the fictionalized outbreak narrative, it is not simply that diseases are blamed on an unfortunate group but that modernization is offered as the antidote to the diseased and dangerous “relics of ‘primitive’ other.”

Outbreak, for instance, opens in a tribal and disease-ridden African jungle space, which is in marked contrast to the next scene, set in the organized, protected, sterile, modern US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID)—the browns and greens of the jungle all the more chaotic when juxtaposed with the white sterility of the laboratory. The village is also full of tribal music, thatched roofs, dying people, and monkeys, while the “virology section” of the USAMRIID is neatly compartmentalized into “biosafety levels,” lists of levels and corresponding viruses distinguishing each section from the next. When the film returns to Africa, this time with the medical researchers, the Westerners walk into the village in their masks and yellow suits, their prophylactics emphasizing their boundaries—metaphorical, technological, and literal—protecting them from the disease and dirt, the dead and dying.

This kind of distancing from a threatening person or group of people continues to be just as relevant offscreen as on. The strident declarations by Donald Trump to ban all Muslims from entering the United States and to deport illegal immigrants are just another manifestation of an attempt to draw a line in the sand between “good people” and “hazardous people,” when, really, those lines have become indistinguishable.

One way to establish security is by literally drawing a line between “good bodies” and “bad bodies,” “good blood” and “bad blood,” and never the two shall mix. This can be done on a legal level, or it can be done with literal lines on the ground, through a quarantine, or by suggestion, through social distancing.

In Outbreak, the entire town of Cedar Creek is quarantined, and then within that quarantine, the sick people are first isolated in the hospital and then fenced into a tented area after they become too contagious to share the hospital. Contagion, rather than using traditional quarantine, depicts the use of social distancing, where individuals are told to remain three feet away from each other at all times. In Containment (CW, 2016), social distancing expands to four to six feet.

Fear of infection makes one especially aware of the distance between bodies, making a suspected carrier feel uncomfortably close. Metaphorical lines are drawn between those who are not infected and those who are deemed infectious or more likely to be infectious. While it may be unattainable, distance from disease is an aspirational ideal. It is no coincidence, Jacqueline Foertsch writes, “that Sir Thomas More’s Utopia is an island before it is anything else . . . The utopic desire for boundaries that hold ignites the rhetoric of the reactionary right throughout the cold war and AIDS eras, with destruction of these seen as equivalent to apocalypse.”

The utopic desire for boundaries that hold continues to ignite political rhetoric. Donald Trump, for instance, argued in an interview with CNN in 2015 that the United States has a “porous border” and that this is not acceptable: “To have a country you have to have a strong border, a really strong border.” He repeated this argument throughout much of his Presidential campaign messaging, including in a TV spot from January 2016. In that particular campaign ad, Trump demanded a temporary ban on Muslims entering the United States (keeping out “the questionable other”), as well as calling for a halt on illegal immigration via Mexico by building a wall (keeping out another type of “questionable other”). He concluded the ad by reiterating the argument that building higher and more effective walls “will make America great again.”

Another example occurred during the November 2014 campaign season, when former senator Scott Brown, running for a senate seat out of New Hampshire, managed to pull all these metaphors together in one dizzying array, predicting that ISIS terrorists would sneak in via “porous” boundaries to spread Ebola, a prediction eerily similar to the plot of Covert One: The Hades Factor.

Unfortunately for Trump, the outbreak narrative demonstrates that boundaries, walls, and safety apparel are never fully effective.

For example: the prison is quarantined on The X-Files episode “F. Emasculata” (Fox, April 28, 1995), but the virus still spreads. The soldiers and the potentially infected are quarantined in The Hades Factor, but the virus still spreads. The hotel is quarantined in season 3 of 24 (Fox, 2001–2010), but the terrorists have more of the virus at their disposal. In Global Effect (Cunningham, 2002), Meredith Tripp (Carolyn Hennesy) attempts to quarantine South Africa, but the virus reaches the United States, anyway. The quarantine is violated in Pandemic and Containment by people defying orders and sneaking out of the containment zone.

Security—and how to maintain it—remains a pervasive theme in all outbreak narratives. The traditional understanding of contagion hinges on the dangers of close contact, underscoring a literal threat to bodily boundaries, but contagion can also be seen as a metaphoric threat for larger, national boundaries. It is a reminder of the inevitability of invasion, exposure, and infection, no matter how high the wall.

I see Dr. Fauci on television and want to scream FOR him.

same.