In his book The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, American art critic Hal Foster writes that it is trauma that allows us to escape from the traditional binary approach that plagued most postwar art: that images either refer to something or try to recreate it. Trauma demanded that contemporary art, fiction, and film make the shift from merely referencing or representing reality to capturing it.

While the traditional binary for art might have been well suited to depicting fantasy and beauty, America in the 1980s demanded something different, something messier. Foster describes America then as full of “fear, anger, and grief related to the AIDS outbreak,” in addition to featuring “systemic poverty and crime” as well as a “broken social contract,” with the rich immune at the top and the poor trapped in poverty at the bottom. During this era, when many felt betrayed by the lies of capitalism and politicians, truth, for artists as well as ordinary citizens, could only be found “in the diseased or damaged body.”

For those navigating the current coronavirus outbreak today, looking at record-breaking unemployment numbers, hearing the frustration of those desperately trying to get tested, reading article after article of our government’s inability to supply protective gear to health workers, much less everyone else, the social contract feels similarly broken, the truth to be found in diseased bodies rather than press conferences.

In the 1980s, the diseased and damaged body was often emaciated and covered with the lesions of Karposi’s sarcoma, while in 2020, we are more likely to see x-rays of lungs filled with sticky mucus, fluid, or even holes created by the immune system’s response to the coronavirus. But both outbreaks—AIDS then, corona now—are measured in body counts and confirmed cases.

Both outbreaks have triggered fury, fear, and frustration.

Both outbreaks have heightened awareness of the immune system—how it works as well as how it fails to work—and they have also turned a spotlight on the failure of governments to protect their citizens. The collapse of our immune system has occurred in tandem with the collapse of political borders, the failures of both to protect and quarantine, and uncomfortable realization of how much our infrastructure has already collapsed.

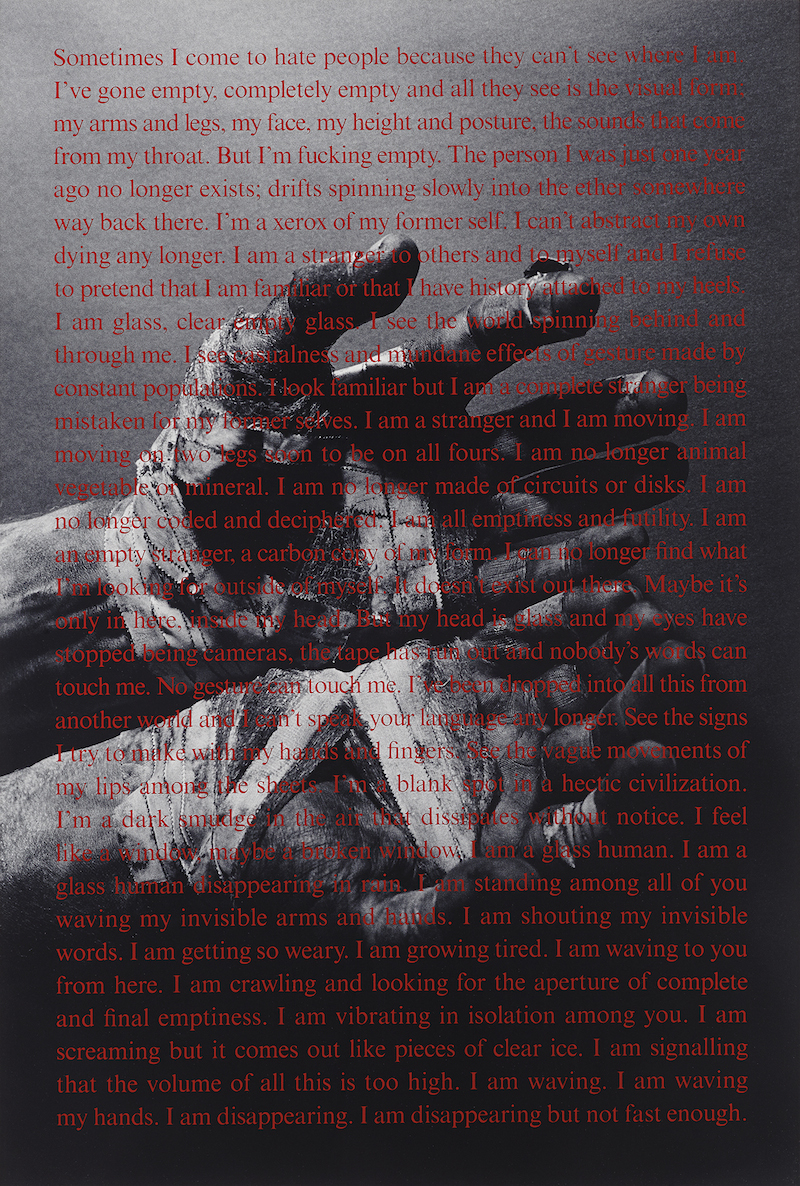

In 1993, I saw an art exhibit at the Washington Project for the Arts entitled “Beyond Loss: Art in the Era of AIDS.” This group show of more than fifty works by twenty-six artists captured the pain and anger, rage and despair not only felt by those artists but also by anyone inhabiting the cultural consciousness. I felt forever transformed as I stood in front of David Wojnarowicz’s image of bandaged hands—palms facing the viewer, as if imploring for assistance—over which text ran, simultaneously an angry tirade as well as the frustrated cries of a man dying and ignored: “I am screaming but it comes out like pieces of clear ice. I am signaling that the volume of all this is too high. I am waving. I am waving my hands. I am disappearing. I am disappearing but not fast enough.”

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Sometimes I come to hate people), 1992

This was my first experience with art that was neither referential or simulacral. This was art that cried out in pain, a pain that grabbed me by the throat and would not let go. This was my experience with the return of the real and, appropriately, it came with trauma.

In many ways, the AIDS crisis feels like it was a lifetime ago. The anger and despair that fueled not only Wojnarowicz and the other artists at the Washington Project for the Arts, but also groups such as Gran Fury and ACT-UP, feels like a footnote in American history, dark days which many would like to forget.

But as they say, history repeats itself.

America in the early 1980s was defined by the posturing of a president more known for his acting career than his political experience, a leader who steadfastly refused not only to lead but even to acknowledge the epidemic until thousands upon thousands of Americans had died. The same conservative wave that put Ronald Reagan in office also reflected a backlash against feminism and civil rights, against the various progressive policies of the Kennedy and Carter eras that had chipped away at the misogyny and racism upon which this country had been built. Reagan built his platform on a determination to destroy abortion and reproduction rights, affirmative action, and countless social service programs.

Ironically, the last few years in America have similarly been defined by the posturing of a president more known for his television career than his political experience, a leader reluctant not only to lead but also to acknowledge the epidemic as not just a liberal hoax. The same conservative wave that put Donald Trump in office also reflected a backlash against feminism and civil rights, against all the various progressive policies of the Obama era that had chipped away at the misogyny and racism upon which this country had been built. He, too, has built his platform on a determination to destroy abortion and reproduction rights, affirmative action, and countless social service programs.

The original inspiration for my book Going Viral: Zombies, Viruses and the End of the World was the trauma of AIDS and specifically the way it affected perceptions of intimacy. After all, I learned about AIDS at the same time I learned about sex. I learned about the pleasures of intimacy at the same time that I learned how it could kill me. That had to have a widespread impact, I thought. Choosing the outbreak narrative on American film and television as my lens, I looked at the ways AIDS would manifest not only in perceptions of intimacy but also perceptions of our government, of the medical community, of immigrants and outsiders, of terrorists and global communication networks.

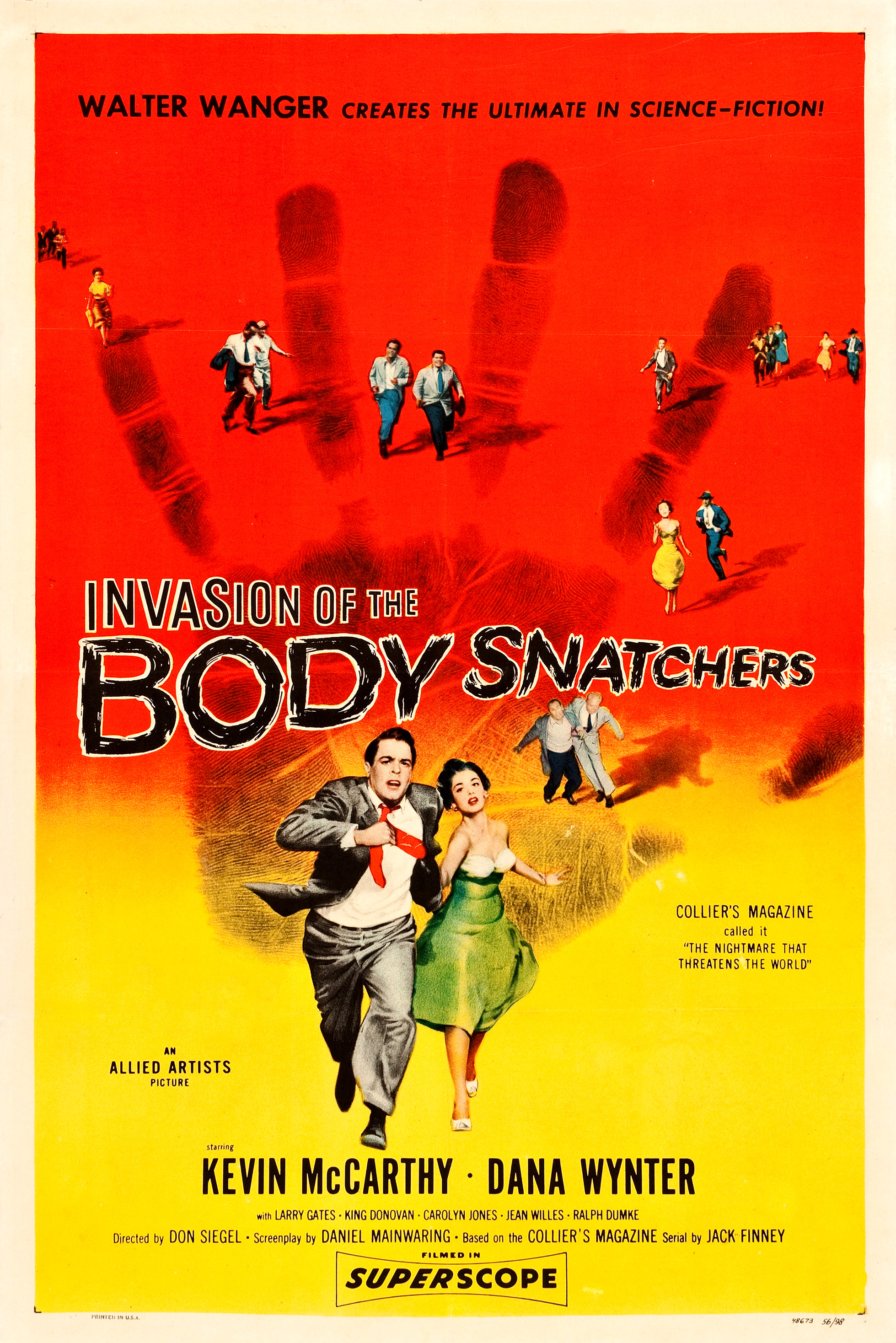

During the 1950s, the language of bodily invasion and immune system failure pervaded film metaphorically. In Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Siegel, 1956), for example, emotionless alien duplicates slowly replace the population of the fictional California town of Santa Mira, and in Invaders from Mars (Menzies, 1953), a young boy realizes that residents of his town are being taken over by aliens. This acted as a metaphor for the imagined threat to the American body politic at the hands of Communism.

However, starting in the 1990s, the outbreak narrative turned these metaphors literal. The threat was no longer from the outside but from the inside, not so much a threat to the body from aliens or monsters or Bolsheviks, but the body literally acting as a threat. Significantly enlarged microscopic views of deadly germs attacking bodily cells became visualizations of this new kind of literal invasion, whether traveling via airplane or boat or terrorist cell.

Whether the outbreak narrative depicts the cultural and social impact of globalization, the increased fear of bioterrorist attack, or the uncomfortable realization that twenty-eight days is all it takes for society to collapse, it continues to provide allegorical and literal reflections of our world, both in the current moment and for the future. The outbreak narrative, in all its incarnations, still reflects an awareness of viral threats, and the inability of immune systems or national borders to protect us, in ways that can be constructive and enlightening to examine.

Because plots within each wave of the outbreak narrative mirror each other so transparently, there is less medium specificity than might exist within the tighter constraints of some film genres, where a television show must be evaluated completely different than a movie. The outbreak narrative is remarkably consistent regardless of whether it is on a television show or a movie, a miniseries or a book. The message is the content, and the medium itself becomes irrelevant; the same story is repurposed regardless of screen size or delivery mechanism: a virus will kill you and no one can save you.

In other words, the outbreak narrative, is not only a rhetorical pattern between individual films but also a pattern that persists across media forms and platforms—television, movies, books, as well as art. It is a story of how our bodies are under attack, a metaphorical fear made literal during the AIDS outbreak before being turned into narratives and images by filmmakers and artists and writers, and a fear that is literal once more.

But before this happened in the outbreak narrative, before this happened in movies like Outbreak (Petersen, 1995) and Formula for Death (Mastroianni, 1995), this was already happening in the art world. Artists, in the era of AIDS, knew firsthand what it felt like to have the threat be on the inside, to have your body unable to protect you and your government ready to ignore you. Now, once more, we know that feeling.

“People looking back give ACT-UP and Gran Fury enormous credit for what we did in terms of AIDS activism,” explains filmmaker and Gran Fury member Tom Kalin. “The real truth is that it was out of self interest and community interest. We were scared to death of dying. It wasn’t abstract, it was right in front of us, in everything we did. We didn’t know how it was transmitted. Every time I brushed my teeth or had sex, I worried I would die from it.”

Now, once more, we know that feeling.

The outbreak narrative, through its fantastical as well as terrifyingly literal depiction of real-life anxieties—on many types of screens, dispersed through many types of networks—continues to provide portrayals of scenarios ripped from our nightmares, our headlines, and our day-to-day realities. What has not felt real since the AIDS outbreak is, once again, upon us.

However, there are significant differences. As Kalin points out, corona is “perversely suited to our 24-hour news cycle,” with its accelerated incubation period, much shorter than HIV in terms of time span between exposure to symptoms. With HIV there was a much longer period until people even realized what was happening, and then it took even longer for people to realize how and why. In comparison, everything with corona has seemingly evolved in the blink of an eye.

“The vicious curve of this is so fast; that’s what is so breathtaking. Within ten days our lives were reoriented,” Kalin describes. We were suddenly “wiping down groceries” and “strategizing how to be in the street.”

Unlike with HIV, to which many had been exposed long before symptoms were visible, long before the New York Times first wrote about AIDS in 1981, now there is worldwide knowledge. “It took a long time for HIV to work its way into every nook and cranny of the country, but everyone now should have the feeling of their own mortality. This is impacting people all over the country,” Kalin continues. “Fear and self-interest and the urge to live are really excellent motivators. That’s why we call them a life force. The urge of the living to live is an important urge. It is how we have survived as a species.”

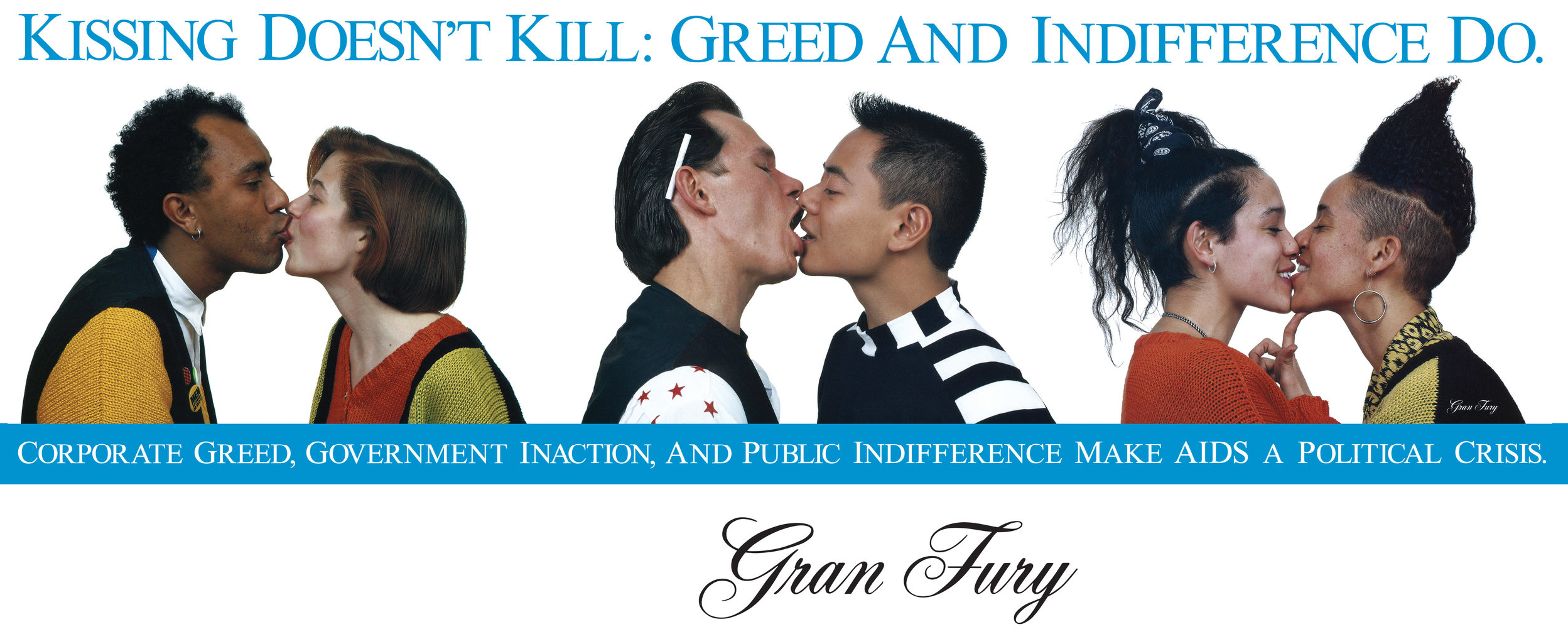

Gran Fury, “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do,” 1989

Gran Fury, “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do,” 1989

Kalin points out that even though Gran Fury’s work is still powerful and effective today and would work in a contemporary meme format (Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do, as shown above, was a political art action that manipulated advertising and media strategies in order to reach a broad audience with information about AIDS and its complex issues), the work was always “just the tip of the iceberg, just a footnote to people using their bodies to change policy or law.”

The rest of the work came from “people lying down at city hall,” doing whatever it took to get people to pay attention. The danger now, Kalin warns, is that memes aren’t necessarily “ruddered in any collective experience.” The memes themselves have become the iceberg.

We cannot forget about the rest of the work — the collective action. Unlike with AIDS, where activism galvanized people to protest, allowing art to be the footnote or the catalyst, with corona, we cannot gather, we cannot protest.

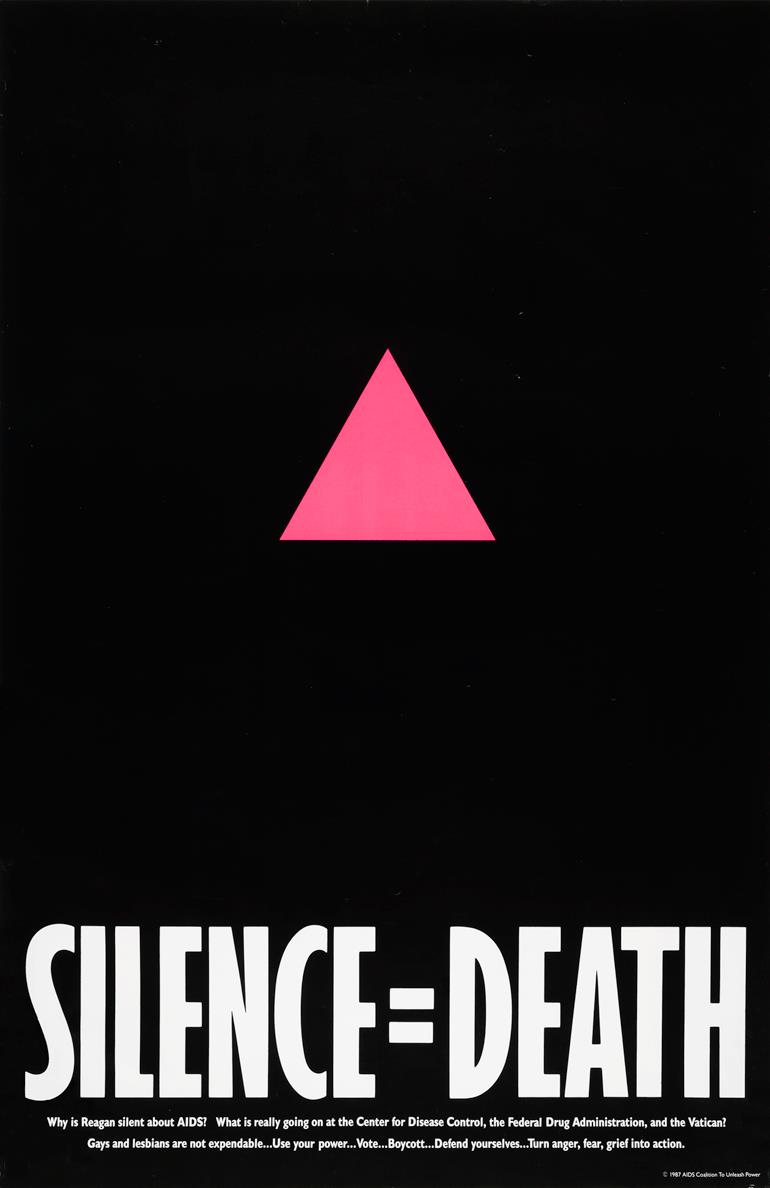

However, as artist group ACT-UP declared during the 1980s and 1990s, silence equals death.

Now, once more, we know that feeling.

“Silence = Death,” created by Avram Finkelstein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Lione, and Jorge Socarrás, 1986, used with permission by ACT-UP.

Recent Comments