When I google reviews of Tár, the first one that comes up proclaims, in all caps, “TAR is a MASTERPIECE.” Subsequent reviews are as glowing if not as effusive. Each one makes me wonder if I saw a different movie.

Directed by Todd Field, who supposedly wrote the film exclusively for Cate Blanchett, Tár tells the tale of composer and conductor Lydia Tár (Blanchett) whose abuse of students, colleagues, and staff leads to the implosion of her career.

Armond White’s summary of the film feels accurate, so I’ll post it here. White writes that director Todd Field “seems torn between endowing her with class advantages and almost vilifying her. She inhabits an NPR world of Millennial privilege — teaching at Juilliard, conducting in Berlin, where she keeps a private abode and lives with violinist-companion Sharon (Nina Hoss) and her school-age daughter. Lydia ruthlessly administers a world-famous orchestra, emulating the high-minded dictates that Anton Walbrook performed with Diaghilev-like aplomb in The Red Shoes.” All of this is true, and probably most viewers of the film would agree with this summary. Then White goes on to critique the movie for being show-offy, with lots of “swashbuckling” and “name-dropping” and “self-parody,” with Cate Blanchett’s Lydia Tár coming off “like an Altman loon who is soon to be exposed.”

Sure, there is some of that. I do appreciate the use of the word “swashbuckling,” in particular, but despite his disregard for the movie, I’m not sure White gets to the heart of the real problems with Tár.

The film makes sure we know, right from the very start, how incredibly brilliant Lydia Tár is. It opens with an onstage interview with real life New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, in which he list her countless accomplishments in such a way that we can’t quite tell if this is supposed to be satire. The audience fawns over Lydia. Adam fawns over Lydia. We, too, might fawn over her if it didn’t feel a bit like she was, indeed, a soon-to-be exposed Altman loon. It all feels like a bit too much, despite the solemnity of the filming, the colors, and the perfection of Lydia’s custom suit.

But then the perfection of Lydia’s life begins to unravel as we, along with others in her diegetic world, begin to discover that her career has been built on abuse, on seducing and discarding young women, and on generally being a terrible person. We watch, for example, as she dangles promises of career advancement in front of her assistant — promises that she seems to find pleasure in never fulfilling. When Lydia bullies a child on the playground, we see the same pattern of abuse she repeats with adults, whom she considers to be equally beneath her. We know she’s using her wife Sharon’s medication while we watch Sharon suffer the consequences of not being able to find her medication, and Lydia lies about where it might be. In one of the film’s best moments, when the editing is especially tight and the dialogue is delightfully sharp, Lydia tears a woke undergraduate to shreds. For a second, you start to think the film might have something to say, might be making a statement about the art world’s elitism, or maybe a critique of identity politics gone too far, of the necessity of separating the art from the artist, of the complexities of distinguishing victims from abusers…but then you realize that no, none of that is happening here. The scene is fun to watch but does not actually bring the movie forward.

And that’s part of the problem. Field doesn’t really commit. The film revolves so much around Tár — to the exclusion, really, of anyone or anything else — that it feels like a one woman show, and yet we don’t know anything about her backstory, which makes it hard to decide exactly how much of a victim she might be, if any. So you’re just left feeling like Tár is more an allegory than a person, although an allegory for what remains unclear.

This makes it hard to feel anything other than indifference toward her, because all you see is a sociopath moving through the paces, lurching toward greater and greater ambition but seemingly for no purpose other than acquiring it. For instance, when Lydia’s career implodes, her failure is made visual by her return to her childhood home, which is working class, a cliched filmic shorthand to emphasize how far she has fallen. Look at the contrast of the perfect Lydia against the weary wood paneling! From such heights to such lows! Etc.

Now, this could have been interesting if fleshed out. Just 18.2% of musicians and visual artists in the UK come from the working class, which could have provided fertile ground for childhood conflict, for sowing the seeds of Tar’s determination and ambition, perhaps the necessity of stepping over people to achieve her dreams. You know, setting up patterns to help explain why she turned out the way she did.

For example, Sadie Powers writes, in her review of the film, “I imagined a younger Lydia, juggling hours of individual daily practice with ensemble rehearsals and a full course load, trying to get scholarships and working jobs, dealing with sexual harassment from old-school music professors with regressive approaches to pedagogy, whilst hearing a chorus of ‘you’re wasting your time’ and ‘we can’t afford to pay your bills when you can’t get a job’ back home. I’ve been there, too, shaving the edges off my accent and observing how I’m ‘supposed’ to act around people born into a higher class, filling my free time in college with editing the school paper and lit mag and serving on committees, joining honor societies, being generally ‘clever’ and ‘precocious,’ all while working nights as dorm security, in the hope that one day I could have the ‘correct’ CV so that I might transcend gender, sexual identity, class, tokenism — hoping that a hand might deign to offer me an opportunity so freely given to white men with ⅔ my qualifications, and it would be undeniable that I had earned it.”

And yet, in a movie that is 2 hours and 38 minutes long, there is no time for this kind of character development. We will just have to leave those bits out in exchange for yet another scene of Lydia jogging through Berlin or having insomnia in her far-too-big apartment.

This makes it all the more important that the only “personal detail” about Tár appears to be her queerness. Everything else in the movie seems exclusively devoted to her career. And yet, other than her sexuality, which is referenced verbally, there’s no real indication of actual queerness since, well, there’s no sex in the movie. For a movie that is seemingly about sex and power, about sexual harassment and sexual abuse, the fact that there is no sex seems like a pretty glaring omission. What is it, exactly, that Lydia gets from these women she uses? The film never shows us. Is it just the thrill of acquisition?

The de-sexualization of the film also begs the question of Lydia’s sexuality. If her gayness doesn’t impact the plot in any way, if there is no sexual component, if there is no aspect of her character defined by her sexuality, then why write her as gay? I mean, other than the fact that she’s married to a woman and not a man, how is the film impacted by the choice to make Lydia gay? Sure, there’s the great UHAUL joke, but other than that, why? Why did Field, when writing this screenplay for Cate Blanchett, think that Tar needed to be gay?

And this is what I found most disturbing about the film.

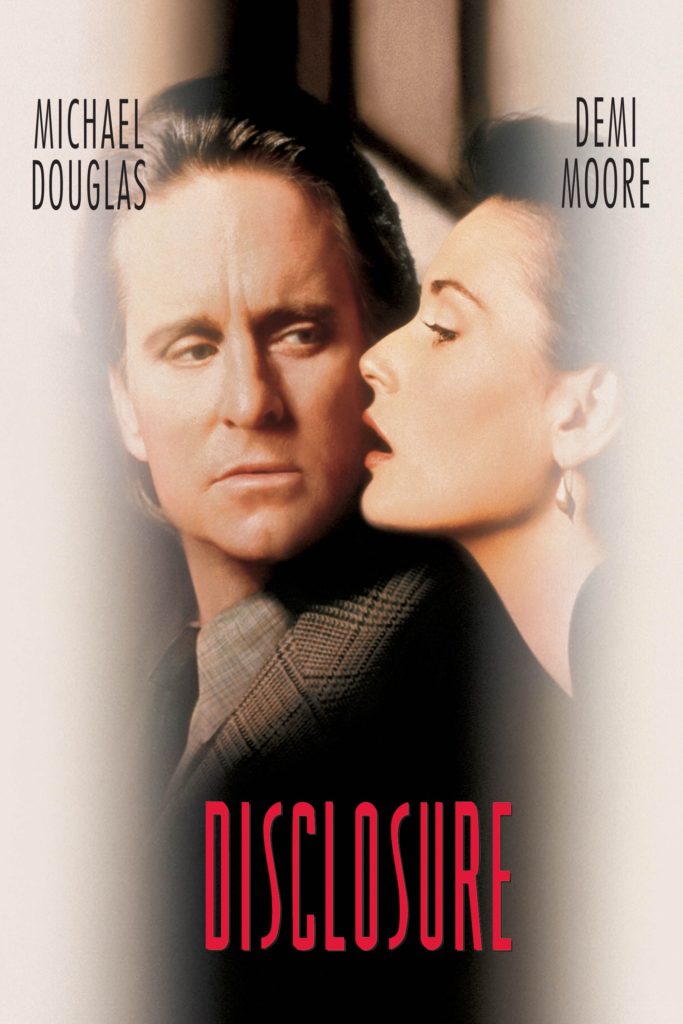

Did Field want to show audiences that the #metoo movement isn’t exclusive to men? And, if so, did Lydia have to be gay to make that point? Or…and this might be the worst option, was making her gay just an easy way to make the film feel edgy and new? Somehow more progressive than 1994’s Disclosure, Barry Levinson’s film about a successful woman (Demi Moore) sexually harassing an employee (Michael Douglas)? Because now! in 2022! we can have a woman sexually abusing other women! (Cue applause!)

And therefore, once we have provided the twist of queerness, we can complicate the #metoo question by showing that (grand reveal) a woman can be just as guilty as a man. And by using the word “complicate” I actually mean the opposite — because, really, we are just repeating the same tropes as in 1994, with a slight tweak of gender.

It begs the question, did Field think that for a power drunk seducer of women to be taken seriously she needed to be perceived as having “masculine” characteristics that would be desirable for women but not so much to straight men? So to keep the film feeling fresh, we get the gorgeous Cate Blanchett with her masculine “codes” — the tailored suits and baseball caps, referring to herself as her daughter’s father, introducing herself as Petra’s “father,” dominating space without any hint of feminine subservience, the predatory pursuit of Olga, the cellist who is half her age. So yes, if Lydia Tár had been Leonard Tár, the movie would have reeked of Harvey Weinstein. And if Lydia Tár had been straight, the movie would have reeked of Disclosure.

So Field does the next best thing, he makes Tár gay. Although, of course, Tár isn’t a UHAUL lesbian (her joke to the contrary), except in the case that she acquires lesbians like pieces of furniture which she throws into her truck and then throws out when she’s done with them.

Because, after all, the other characters in the film are just pieces of furniture for Tár’s consumption. As Heather Hogan points out for Autostraddle, “Field is intent on mocking any real critics of his or Lydia’s opinion on artistic geniuses. He even refuses to bring them into focus, literally. Their faces are blurred; we can’t tell if Lydia is remembering misdeeds or tripping over her own fears; and we never see the perspective of the women Lydia has seduced and discarded. Tár is rooted firmly in Lydia’s perspective, intent on preserving her legacy above all else.”

And this is where Tár goes so wrong. After all, the film should be about tearing down her legacy and putting something (or someone) better in its place. Instead, we’ve just got Disclosure with a makeover.

Recent Comments